@adlrocha - Reflecting on the future of research, academia, and innovation.

Ideas for improvement

I’ve read this past week a set of unrelated articles that have pushed me to write this publication and share this reflection with you all.

There are a lot of conflicting opinions on what will be the impact of COVID on the world and our daily lives. Many say that remote work is here to stay, and that what we’ve experienced so far professionally will change the job market as we know it. Others theorize that COVID will make us afraid of living in big cities and we are all going to come back to our home towns, or move out to rural areas. The most skeptical say that we will come back to normal like nothing has happened. And the most pessimistic ones claim that we will be at home attached to a face mask for the rest of our lives.

I don’t know about all of this, but what is clear is that the pandemic is at the same time a touch of attention and an opportunity to rethink many of our current social systems. A few weeks ago I presented my opinion on social reward systems, and how I think many of them are currently broken. Today I am going to build upon this idea zooming in on research, academia, and innovation.

“This pandemic is a force that is pushing back human progress, no less than World War II.” - Jack Ma

Jack Ma’s speech

“Many regulatory authorities around the world have become zero risk, their own departments have become zero risk, but the entire economy has become risky, the whole society has become risky. The competition of the future is a competition of innovation, not a competition of regulatory skills.”

This is Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, in his last speech at the Bund Finance Summit talking about innovation, regulation, and the future of the financial system. The speech is full of insightful and controversial ideas. This was the first seed of the article. After reading his speech two main ideas resonated with me.

Idea #1: Innovation and research should be focused on building things that we will need decades from now, solving the big problems of the future. We shouldn’t build for the present but for the future.

“It's true that today's finance doesn't need digital currencies, but it will need them tomorrow, it will need them in the future, thousands of developing countries and young people will need them, and we should ask ourselves, what real problems are digital currencies going to need to solve in the future?”

In this statement we find the first discrepancy between our research and innovation reward systems, and the desired outcomes. We don’t invest the time and the money anymore on building the future, we only focus on generating near-term impact. First, we have researchers that need to publish academic papers in order to read their thesis and keep their grants, what leads them to end up focusing on shallow and incremental research rather than on important long-term problems.

Then, we have companies exclusively looking to invest in research that can lead to profits in the next one or two quarters. With these short time frames, the research we are doing is only focused on the present, and not in the problems of the future.

Research and academia should be focused on solving the problems with the highest expected impact in our future lives, and mobilize the resources accordingly to allow researchers to freely focus on solving it without external constraints. If we don’t do this we will keep building the equivalent to the technical debt of research and innovation. And you may be wondering, who chooses what is important for the future and what not? I’ll try to give a potential answer in the next idea.

Idea #2: Regulations should be designed for the future and not the present. Policy making is a technical problem.

“Our research institutions should not be policy institutions, nor should policy institutions rely only on their own research institutions. Because the digital currency system is a technology problem, but not only a technology problem. It’s also a solution to future problems. [...] Policy making is a technocratic job to solve systematically complex problems.”

What degrees and experience do our politicians and policy makers usually have? I don’t know about your countries, but in mine they are either lawyers, economists, psychologists, philosophers, or they don’t have a degree at all. Unfortunately we don’t have that many engineers, biologists, or physicists, but still they are the ones in charge of regulating the technical innovations in these fields. They may be advised by experts in the field, but when presented with different alternatives I don’t think they would have the knowledge to choose what’s best for the future.

I believe that in many cases we try to be protective with the regulations we design for new technologies. Policy makers focus on protecting the present, preventing experimentation and development instead of regulating for the future. More lax regulations, or future-oriented ones, would allow researchers and innovators to tinker with new ideas while protecting the future.

I know, I know, it is easier said than done and there is infinite casuistry, but maybe really making policy makers and researchers work together (something they say they already do, but that I don’t personally believe) could help us avoid regulation from delaying innovation.

So to the question above about who should choose the problems that are important for the future? Definitely not inexperienced politicians and policy makers. I’d prefer this decision to be made by experts in the field.

Pfizer’s CEO

Idea #3: Scientists and researchers should be free of burden in order for them to do their best possible job.

"I wanted to liberate our scientists from any bureaucracy. When you get money from someone, that always comes with strings. They want to see how we are growing to progress, what types of moves you are going to do. They want reports. I didn't want to have any of that."

The second seed of the article was planted by this statement from Pfizer’s CEO where he claimed that he rejected any public money for their COVID vaccine research in order to free their scientists. It is impossible to be 100% creative and focused if you have to worry about publishing papers, renewing your research grant, or other types of bureaucracy. I completely support Pfizer’s CEOs decision. If we want research institutions, and researchers as a whole to be able to do their best possible work, we must free them from all the unnecessary burden that the system currently puts upon them. And if you’ve been following the news around Pfizer and COVID vaccines this past week, this seems to have worked out (at least for now).

Investments in research and innovation should be designed to free researchers. Actually, this will make the ROI of the investment way higher than if we load researchers with useless work and we distract them from making their high impact job.

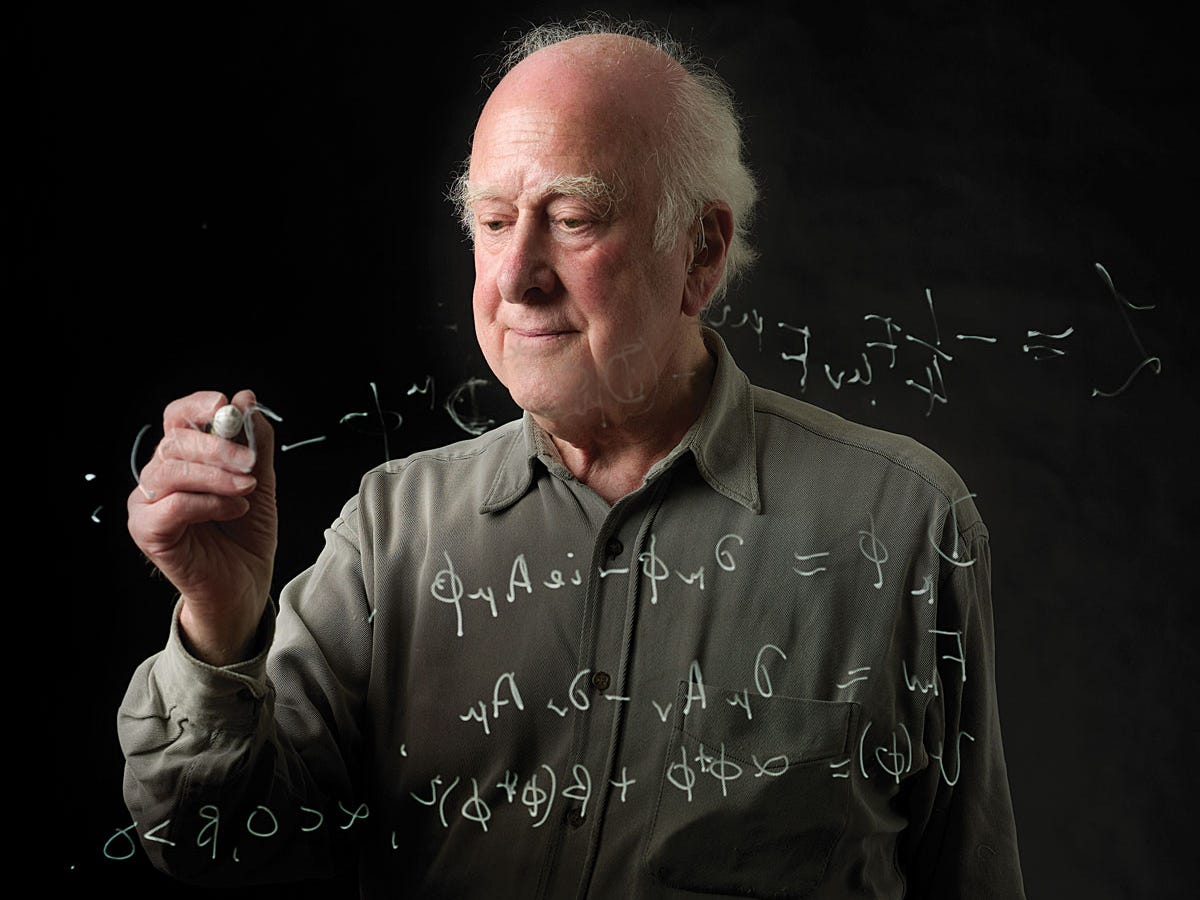

Peter Higgs

Idea #4: The academic reward system is broken.

“It's difficult to imagine how I would ever have enough peace and quiet in the present sort of climate to do what I did in 1964. I wouldn't be productive enough for today's academic system” - Peter Higgs

I know, I keep repeating myself, but it is something that really bothers me. What do we want with research, to achieve groundbreaking results that enable science to advance like what Peter Higgs did with his particle? Or do we want to have professional paper publishers? Papers which in many cases end up at the bottom of a drawer without any application nor future development. Even a veteran like Peter Higgs admits that he wouldn’t have been able to survive (even less discover his particle) in the current academic system.

We need to change the way we recognize researchers. I personally prefer an impactful researcher that makes advances for the state of the art in his field than a prolific one that publishes a lot of shallow papers (actually I’d rather have a prolific and impactful one, but you know).

Consequently, we may need to change researcher KPIs and reward systems to incentivize impact. Could “cites” be a better metric to recognize a researcher than “number of papers”? I don’t know but this is something we need to fix soon.

And don’t get me wrong, publishing papers and attending conferences is awesome, and required, in my opinion, to do good research. It triggers conversations, interesting discussions, attracts feedback and criticism, and sparks ideas in others. But the sake of a researcher shouldn’t be exclusively to publish papers and attend conferences.

"Please give a list of your recent publications." Higgs said: "I would send back a statement: 'None.' "

An academic Substack

Idea #5: The barriers to publishing peer-reviewed (and good research) papers must be lowered.

“But the academic work I have done on my own time frequently remains unpublished, since the media available to us researchers are obsolete, overly exclusive or subject to market demands incompatible with real science. I want to spread the word, but I prefer not to contribute my hard work to a system that is so exclusionary.

Access to journals is prohibitively expensive and therefore practically unavailable to independent researchers.

Apart from the financial walls that academic publishers encourage, there are frequently de facto barriers to participation as a contributor, reviewer, or consumer of published work.

The review process itself may be subject to intellectual protectionism and even unintentional gatekeeping that prevents research from reaching a broader audience that can help the ideas grow.”

Source: https://jfmcdonald.substack.com/p/academic-substack-open-free-and-subject

Maybe this idea from JFMcDonald of an academic Substack could be the perfect foundation to start redesigning the academic system and aligning the rewards to what we want to get from research, academia, and innovation.

Actually, a few months ago I started a public Github repo with ideas, links, and papers, for other’s to check and contribute to. I track in the issues some of the ideas I want to develop and to openly discuss with others. I recently added this idea of an academic Substack to see if it sparks interest, and I find a bunch of contributors to start building it as a side project.

The same way DeFi (Decentralized Finance) appeared to redesign a broken financial system, we should start designing DeRe (Decentralized Research) initiatives to redesign a broken academic system. My initial idea would be to design a system that fosters collaboration between different research institutions and research groups. Which offers a common (and linked) knowledge base for all the research community with access to published papers, and collaborative and objective peer-reviewing processes, maybe even including the ability to easily organize and run remote conferences around “paper calls”.

In short, a lot of crazy ideas that I will leave for some other day in order not to extend this publication too much (but that we can start discussing in the issue of my ideas repo).

It’s time to rethink research and academia

We are using the COVID pandemic as an excuse —or the forced reason— to revise many of our current systems, values, and processes. Why not including research and academia to this list? See you next week!